Excerpt from “A Hole for a Landscape, and a Smell of a Hole”

Tomohiro Masuda, Curator of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

For this exhibition, Tomohito Ishii presented a video art that documented his “hole digging” performance at an empty land in Tama Newtown(1), where he was born and raised. Tama Newtown is the largest housing project in Japan that aimed to construct a residential complex at the outskirts of Tokyo. However, the project was abruptly discontinued during the middle of the construction phase, leaving a portion of the territory unattended for decades. Produced by mixture of dirt and concrete, the thick surface layer of this artificial ground is extremely solid and impenetrable. Each time Ishii forcefully dug the earth with a shovel, a sense of futility accompanied the shrill sound of metallic clank. One felt the sense of futility because the developed land conceals the ancient memory that the region is known to preserve. When the sea level rose during the Holocene glacial retreat, the Tama hillside remained a dry and resourceful land for the prehistoric culture of the Jōmon period (12,000 BC – 300 BC) to flourish. Since archaeologists have discovered numerous ancient remains, Tama has been acknowledged as a historical site that stores the memories and spirit of the antiquity. However, the landscape in which Ishii physically and painstakingly engaged himself was artificially constructed by piling up soil, dirt, and concrete, layer upon layer. One may dig in, but no relic of old or recent past can possibly come out from such barren earth.

After he laboriously dug a reasonable depth, Ishii threw himself naked into the hole. Similar to many of the residents of the Tama Newtown, Ishii’s family was originally an outsider to this neighborhood. Although Ishii was born in Tama, he cannot feel a strong bond to the local community. Therefore, the fertility of “hole digging” and the ludicrousness of the naked body in this artificial landscape, which his video work represents, is the portrait of the artist, the residents of the Newtown, and perhaps of modern human, who’s existence is alienated from the memory of region. For the residents of the Newtown, Tama’s original and primordial scenery is no longer accessible, because it is buried beneath the Sanrio Puroland(2) Theme Park and other commercial infrastructures. Or perhaps we can argue that the Theme Park has become the region’s original scenery. People who can criticize this alteration as terrifying are blessed because they have a home to return – a home that is isolated from the suburban shopping mall and the touristy sites of the old town; home that are free from the capitalist society in which any criticism against the spectacle is no longer effective. Or they are blessed because they are unaware about such state of our contemporary society.

……..

The sense of hope and despair was already recognizable in the photographic image of weeds that Ishii displayed in the exhibition Railroad Siding(3) that was held last summer. The photography captured weeds that grew at the empty land of Tama Newtown, where Ishii performed his “hole digging.” It’s earth, which is mixed with gravel and cement, was thought to be too barren for any type of vegetation to grow. However, after his performance the soil turned soft enough for the plant to sprout. The image of this nameless grass seemed extremely bright to me. I wonder how high and rampant the plant would grow, especially after it has inhaled the odor of the hole. Or rather, now that we have dug the hole on the ground, it became our mission to make a flower bloom. Like the protagonist of Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle(4), we now have a strange blue mark on our cheek.

(1)Tama New Town Project – the largest residential housing development in Japan, which was launched in the 1960s. The development involved a massive land reclamation that destroyed old settlements and villages. In 1971, the first population moved in to the newly built residential complexes.

(2)Sanrio Puroland – an indoors themed park that opened in Tama New Town in 1990. Puroland is known for its attractions, events, and merchandise that use popular Japanese characters such as Hello Kitty. The park is often compared with Disney Land.

(3)A Railroad Siding ― a biennale format independent exhibition organized in 2015 by artists and critics.

(4)The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle – a 1994 novel written by Haruki Murakami. An empty well appears throughout the story as a symbolic motif. More than a structure to withdraw underground water, the deep hole represents an imaginative channel that connects life and afterlife, past and present, Japan and China. The protagonist’s cheek is bruised after he enters and passes through the well.

「風景のための穴と穴の匂い」 より抜粋

桝田倫広

ー前略ー

石井は、自身が生まれ育った多摩ニュータウンの空き地で穴を掘った映像を展示した。団地を建設するために盛土され、結果、そのまま何十年も放置されることとなった空き地の土はコンクリートや土砂が混じり、このうえなく固く、地面に突きたてるスコップは鋭い金属音をたてる。掘削からは無機質な徒労感が伝わってくる。というのも縄文海進時でさえ陸地だった多摩丘陵は、縄文時代の遺跡が多数発掘されているように、古代の記憶に満ちているが、彼がスコップを突きたてる大地は、そのうえに無造作に土砂の積み固められた造成地である。どこからやってきたかさえ知れない盛土によって固められた高台を掘ったところで、古代どころか近過去の遺物さえ出てこない。それでも石井は、苦労して掘った穴がそれなりの深さに達したあと、おもむろに裸になり自らの身体を穴のなかに投げ入れる。しかしそれもまた著しく無意味なことだろう。多くの多摩ニュータウン在住者と同じように、石井の一族は決してこの地で生まれたわけではない。同地で生まれはしたものの、石井はここに地縁がない。この映像のなかで展開される石井の穴掘りの不毛さや、無機質な風景のなかで晒される裸体の滑稽さは、そうした土地の記憶とは一切無縁である石井の、あるいはニュータウン在住者の、いや、こういってよければ現代人の姿を象徴している。ニュータウンに住む、ぼくらの帰るべき原風景は当の昔に、ピューロランドの下に消えてしまった。むしろピューロランドそのものなのだと言ってしかるべきかもしれない。そのことをおぞましいと否定できる人間は、とても幸せである。なぜならその彼(女)は、郊外のショッピングモールや、もはや観光地化された下町以外に、言い換えれば、最早スペクタクルという批判が無力であるほどに一分の隙もなく資本に浸された地から隔絶したところに帰るべき故郷を持っているか、あるいはそんな現代の状況に気付いていないだけなのだから。

ー中略ー

それでも希望 、あるいは絶望は、昨年の夏、石井が引込線の展示の際に提出した雑草を撮ったイメージに徴候的に表れていた。その写真はかつて彼が多摩ニュータウンに掘り、そして埋めた穴の跡地とそこから映え出した雑草を写したものだ。砂利混じりの不毛な大地のなか、穴の跡地、つまり掘り返されて土が柔らかくなった部分にだけ、雑草が生え始めたのだった。その名もなき雑草の姿は、私の目にはとても眩しく見えた。穴の匂いを吸いこんだ雑草は、これからどこまで高く伸びるか、どこまで茂ることができるのか。というよりも、穴を掘りおこしてしまった以上、そこに花を咲かせることが私たちの使命となった。『ねじまき鳥クロニクル』の主人公のように、私たちの頬にはあざができてしまったのだ。

Excerpt from “The Distortion of the Hole, I Tumble Down – at the Hillside”

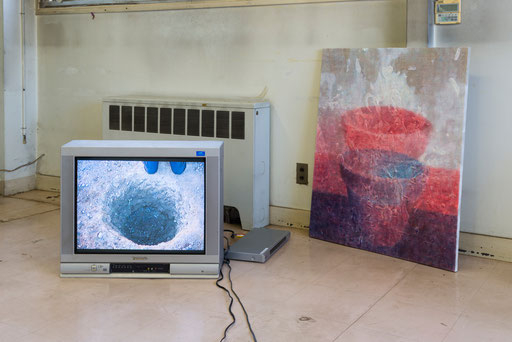

The spatial vacancy and the topology of a hole reminded me of a particular motif. And this topology seems to be the main motivation for me to visit and perform “hole digging” at this specific site. I associate the spatial properties of a hole with a motif of a potted plant. While a pot strongly suggests the constraints of artificial space, it also shows the functional capacity to internalize every possible materials or substances. The uniqueness of a pot is that it transforms plants, a static living organism rooted in a ground, into something transferable and mobile. And this mobility is guaranteed by the closedness of the pot. What fascinates me most by associating the motifs of a hole and flowerpot is their shared topology of discontinuity and continuity generated by the emptiness of space.

Sometime ago I became strongly interested in ordinary houseplants that are cultivated and displayed in pots, whether they are situated indoors or outdoors. Observing these plants that are displaced from nature and transplanted in people’s dwelling environment made me feel that something significant was occurring. I felt that these plants were the alter egos of the people who inhabit the same space.

The association between hole and pot suggested a hypothesis that our human lives are also grown and nurtured in an arbitrary closed environment. In other words, because people were deliberately transplanted in this artificial space of Tama hillside, our existence and human agency cannot neglect people’s arbitrary intentions. I assume that this is the reason that I cannot take my eyes away from houseplants. Pots represent another form of artificial orifice that can contain anything; a potted plant symbolizes our human lives that have been transplanted into a different space.

"Human/Vegetable"

@ Ex-Tokorozawa Meal Center, 2015

Photo by Ken Kato